The npm blog has been discontinued.

Updates from the npm team are now published on the GitHub Blog and the GitHub Changelog.

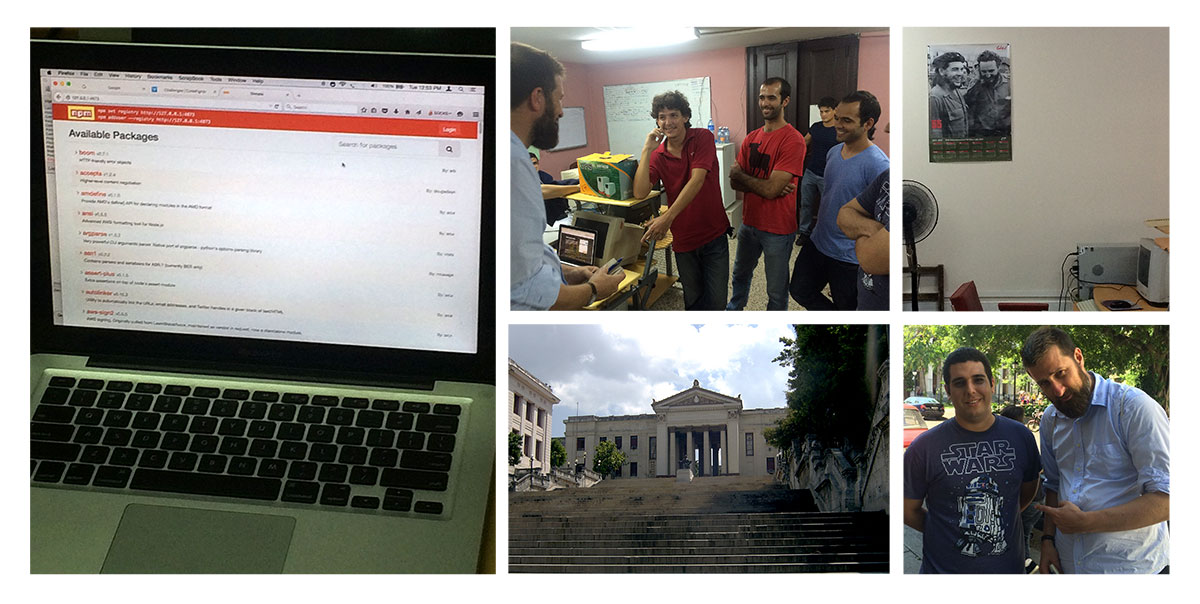

La Habana Affair

I just returned from a great trip to Havana, and I can report without a doubt: Cuba is such an exciting and vibrant country on the verge of a(nother) revolution in their connections with the greater world. I’m really excited to see what the next decade brings for the empowered youth and how they process the change that’s about to wash upon their shores.

Here are some notes from the trip.

We had high hopes of delivering Los Paquetes of open source software and freedom, burned onto a few dozen thumb drives. Unfortunately, these were stifled somewhat at the airport.

Apparently, there exists a ledger of what, and how much, can be brought into Cuba at any given point, unbeknownst to the casual tourist. As I passed through the customs line, I dutifully itemized everything I had brought, all of which was nicely packaged and consolidated in a single wombat-themed npm sock. Unfortunately, I exceeded the items in this “ledger of allotment” by 33 thumb drives, 3 smart phones and 4 baseballs (!). It didn’t seem relevant that the flash memory in my personal camera and phone contained more GBs than all of the confiscated thumb drives combined.

To their credit, Cuban officials couldn’t have been nicer about taking the contraband, itemizing it in triplicate, placing everything in a burlap sack with double security ties, and putting it into a warehouse for eternal safekeeping. The whole process took only three short hours!

The good news is that I did succeed in bringing in a few thumb drives, on which were Tor clients, NodeSchool modules, a lightweight Linux distro, the movie Revolution OS, and a downsampled version of Laurie’s Stuff Everyone Knows talk. This meant I did have a few gifts such as the allowed thumbdrives, stickers, wombat socks and battery chargers for when I went to meet with my new comrades at the University of Havana’s School of Computer Science — just not enough to really spread the free-market love.

When we arrived at the university, a nice man noticed us looking for the CS department and offered a quick tour of the building, on which there was a balcony where Fidel himself had orated. He then found a friend who took us on a walking tour of the surrounding student neighborhoods, guided us to a bar / house where Castro used to live, pumped us full of Negronis, and finally hit us up for money — all this from a supposed Spanish professor!

Lesson learned: be very careful whom you ask for directions, or you’ll wind up a bit tipsy and a few Cuban Pesos lighter.

Back on track at the University and free of our diversions, we finally found the droids we were looking for, and enjoyed a good hour or so with about a dozen students. Here are a few things we learned and observed:

- If you’re an admin in the CS school, you’ve got good access to the web.We saw streaming video of American baseball games and other examples of high-bandwidth usage. Normal students? Not so much: you’re relegated to an allotment each week of what can be downloaded. Speeds are typically between 2 - 10mbps, and their only source of traffic is Venezuela’s undersea single T1 line.

- Just getting onto the web requires routing through a number of proxy servers. I’m not sure if this was through necessity or merely a preference for a non-monitored environment.

- The hardware wasn’t as archaic as I had expected: laptops maybe 2–3 years old. I only saw one Mac (Apple seems to be the premium brand throughout Cuba) — but their computer labs were not too dissimilar from many of the less tech-savvy higher education institutions here in the US. As with the Cuba’s ubiquitous classic cars, there were several visible attempts to patch together pieces and parts to make a working desktop server. Nothing goes to waste in Cuban society, especially not electronics.

- Facebook only caught on a few months ago and has been spreading quickly over the summer. Twitter is not a fully-realized method of widespread communication yet:they’re not quite sure how to use it; in addition, Twitter in its current state is too cumbersome and slow to access via the browser. Applications like TweetDeck are a great workaround, as they’re not kneecapped by slowness from the government monitoring that is likely taking place upon the direct access.

- There’s an illegal, offline internet called SNET, whose contents are slurped into a Lucene database: whole versions of sites like Wikipedia, StackOverflow and other more entertainment-based content. I got the sense that there were those in the room that might have helped this project along.

- The students had built their own version of the npm registry! All the old favorites were there, like Gulp and Express. There even had a few node projects up and running, and were certainly apt to know more. We’re going to try to do some extended learning and possibly conference them in for a talk in the near future.

The importance of the connected society for Cuba was clear. Even intermittent access to the Internet via WiFi was creating new community centers throughout the country. What a benefit it might be to own a business nearby one of these chosen corners.

Walking along the Melacón (sea wall), you’ll find clusters of people on one block, and none on the other. The reason was clear, whether it was the plaza square of a small agricultural town or in the center of Havana:people congregate with their laptops, tablets, and phones wherever there’s a signal. However, there exist only 35 of those hotspots in a country of 11 million.

Unfortunately, the cost of this service is still prohibitively high — and try using your laptop for work with no power outlet, in full sunlight, under 100% humidity, with frequent torrential rain showers rolling through with tropical force. This doesn’t speak much for a nation’s hope in general productivity.

What this means is, like my introduction to Cuba through multiple, stamped custom forms in carbon triplicate, there is both a charm and challenge to the old ways. There are aspects of Cuban society that truly are in a time warp, and often done purposefully so.

When the next Cuban revolution begins (either slowly or in upheaval), it will be led by these, the next generation of technorati, who have taught themselves how to access and leverage information freely. For now, this access remains unique to a small percentage of the population, but the students we met can’t be far removed from becoming future revolutionaries, as they’re too smart and resourceful to do otherwise.